Howard’s 35th annual James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art and Art of the African Diaspora honored the legacy of Elizabeth Catlett, the renowned sculptor, printmaker, activist and Howard alumna.

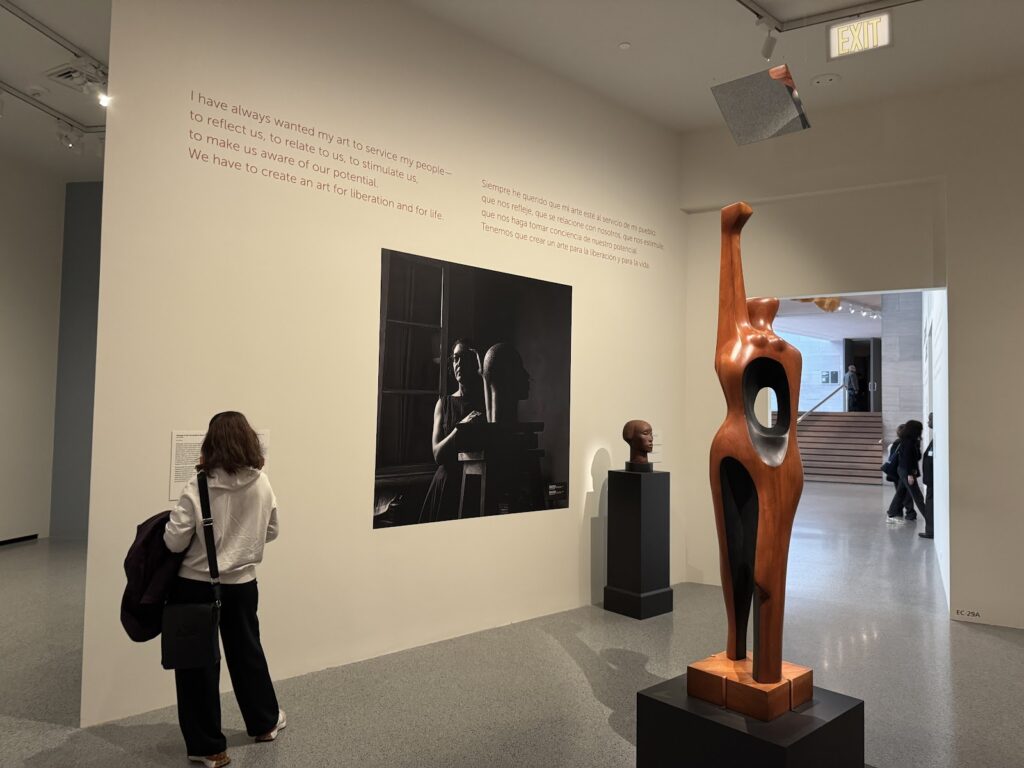

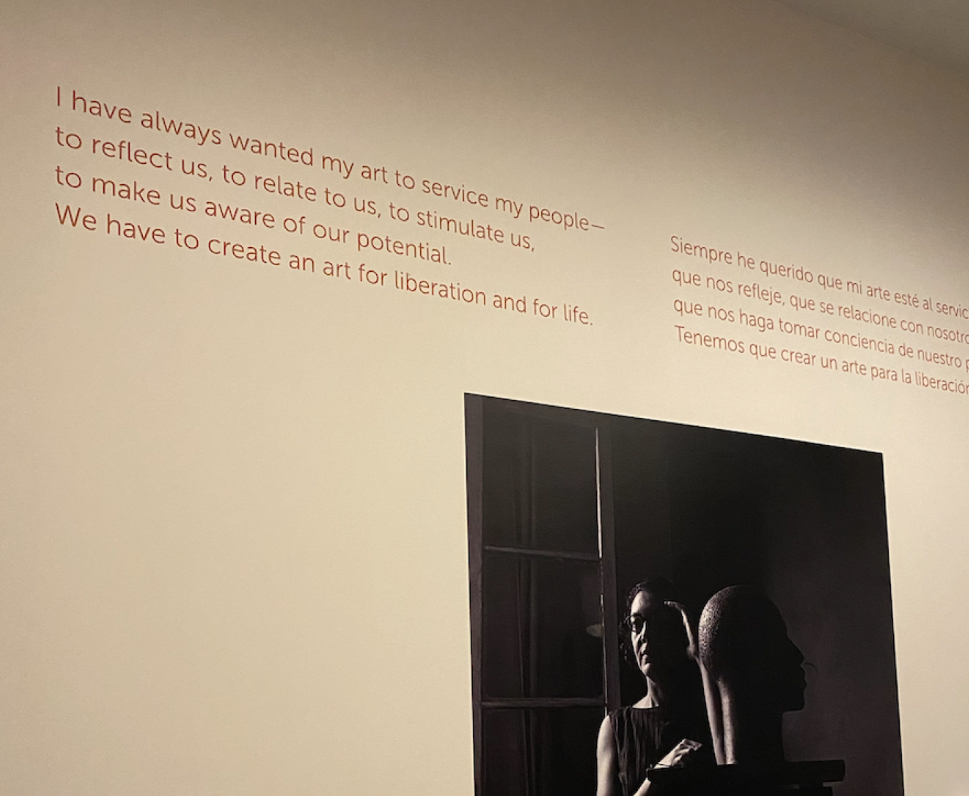

As a pioneer in the art world, she is known for work that honors human dignity and freedom.

As part of the colloquium, the event featuring the landmark English and Spanish exhibition was held on April 5 at the National Gallery of Art.

Before entering, guests were met with bold letters: “Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist.” At the check-in, bilingual pamphlets set the tone for the afternoon, giving attendees a glimpse into her world.

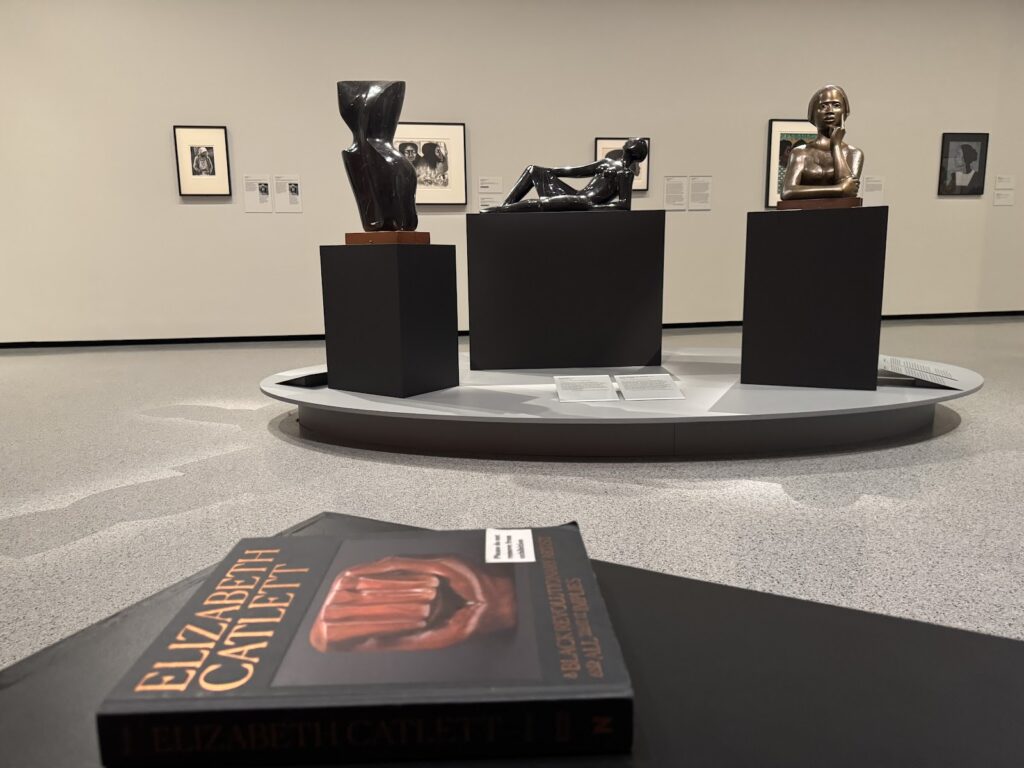

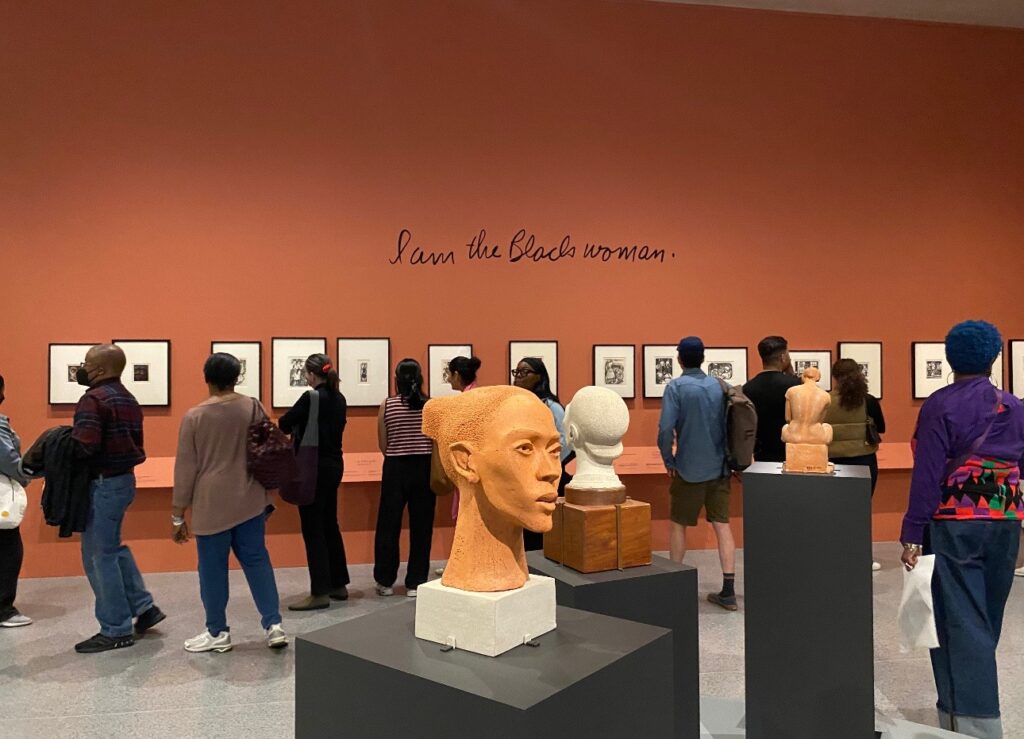

Sculptures hung from the ceiling and prints lined cream and earth-toned walls. In one corner stood an interactive collage station that invited attendees to pay tribute to one of the various mediums Catlett mastered.

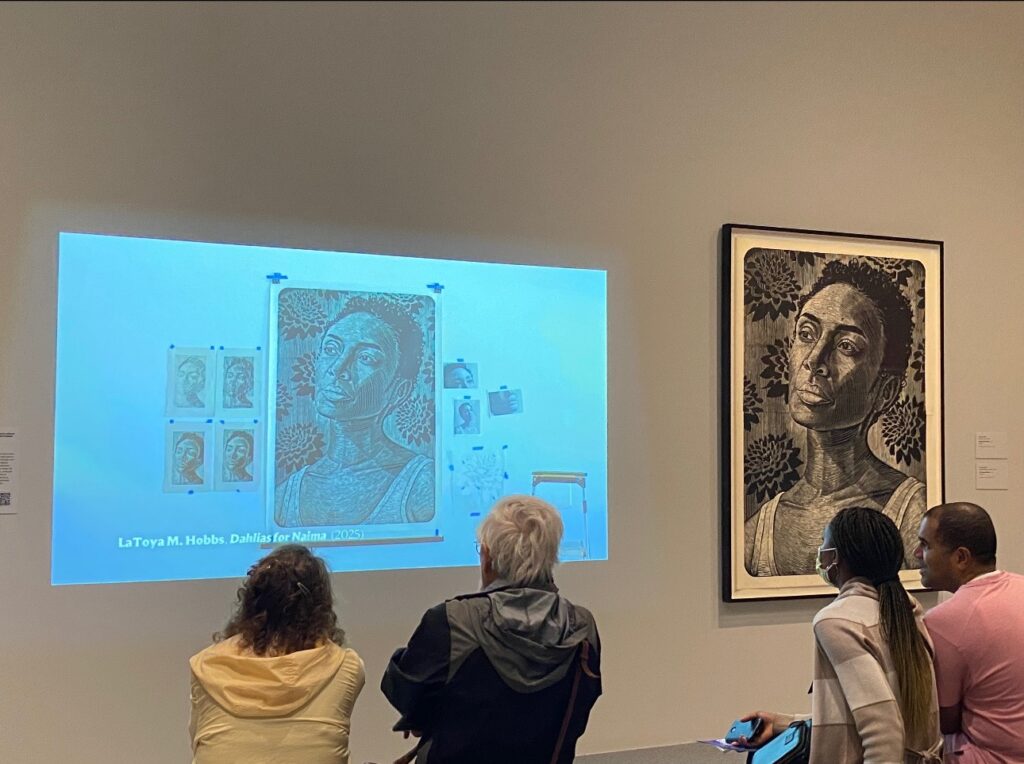

This retrospective, the largest ever dedicated to a Black artist, showcases over 150 rarely seen paintings, prints, sculptures and drawings and marks a historic collaboration between Howard and the National Gallery.

Howard has long celebrated Catlett’s work, one way being by commissioning Catlett for “Students Aspire,” a sculpture found in the university’s College of Engineering and Architecture.

Attendees smiled and stood engaged with wide eyes, reading the words and observing the pieces. Conversations erupted as guests engaged with the exhibit’s diverse themes, from “Target Practice” and “Black Unity” to “Mother and Child.

The exhibit, which runs until July 6, offers a comprehensive look at Catlett’s journey—from her roots in Washington, D.C., to her transformative decades spent in Mexico, where her art consistently challenged systems of injustice.

After studying at Howard and the University of Iowa, and becoming the first U.S. citizen to hold a master’s in fine arts, Catlett moved to Mexico in 1946. In 1959, she became barred from reentering the United States and in 1962 she was stripped of her citizenship.

She then joined the Taller de Gráfica Popular and became a Mexican citizen in 1962. Her work celebrates the resilience of Black and Mexican communities.

This was reflected in the museum’s curation as artwork descriptions to Catlett’s own quotes were both in English and Spanish, honoring her “two peoples.”

Through reflections from her family, collaborators and scholars, attendees were invited to not only remember Catlett’s art but to carry her commitment to justice, education and “art for the people.”

The afternoon began with an intimate look at Catlett’s process and creative collaborations. Her son and studio assistant of 50 years, David Mora Catlett, sat down with art historian J.V. Decemvirale to share stories of her practice and philosophies.

Mora Catlett explained that her goal was to create art that everyday people could connect with, regardless of background or their ability to visit museums.

“To her, it wasn’t just about expressing an idea or making a statement. It had to be [about] giving it to the people,” Catlett said.

The second panel, “A Sense of Purpose and Integrity” featured K.E. Coney-Ali, co-director of the Howard University Gallery of Art, Melanie Herzog, and Lowery Stokes Sims reflecting on Catlett’s political courage, teaching and lifelong commitment to representing Black people with dignity and power.

“I always say that I was scared sh-tless of her before I met her,” Sims admitted to laughter from the audience. “Elizabeth Catlett was willing to put her life and her career on the line for her beliefs.”

Coney-Ali spoke on Catlett’s involvement with “The Black Experience,” a landmark exhibition that debuted in Mexico City in 1970 and eventually toured through California and the Studio Museum in Harlem before landing at Howard—making it the first historically Black college or university to host the show.

“She felt that it was important that they saw themselves,” Coney-Ali said, referencing the students and faculty. “That they understood this idea of civil rights and being able to transition from the New Deal era of black and white. into color in the 1970s.”

This same intentionality extended to works like “Target Practice,” which Coney-Ali described as a powerful visual indictment of anti-Black violence.

“She took that sculpture and turned it into this just sharp form of direct social commentary,” Herzog added.

Sims closed with a story that perhaps best encapsulates Catlett’s spirit: a bus trip she took with her students while teaching in New Orleans. The route to the museum passed through City Park, a segregated area.

“So what she did was, she drove the bus to the steps of the museum, so technically they would not put a foot in the park,” Sims said. “And they were able to go to the museum.”

The Howard Gospel Choir took the stage following the second panel, delivering a performance to tie the day’s themes together through sound.

The program continued with a virtual presentation by filmmaker Juan Mora Catlett, Elizabeth Catlett’s son. Through excerpts from his films “Betty y Pancho” and “EC: The Work of Elizabeth Catlett,” he reflected on her legacy as a revolutionary artist, mother and creative partner.

The final panel brought together four of Elizabeth Catlett’s granddaughters, Naima, Nia, Ifé and Crystal Mora, a reflection on Catlett’s life and legacy. The panel discussion was moderated by Terence Keel, an award-winning professor at the University of California Los Angeles and Ifé’s husband.

Naima shared how growing up between Detroit and Mexico gave her a “sense of liberation from a very young age,” and shaped her understanding of the world. Unlike many of her contemporaries who went to Europe, Catlett found solidarity with other brown communities in Mexico in the 1940s.

Each of her granddaughters expressed that Catlett influenced their lives and the work they do today, teaching them about finding solidarity with other brown people, healing trauma in marginalized communities and fearlessness.

The granddaughters concluded that Elizabeth Catlett’s legacy belongs to everyone, not just them.

“If one person walks away and says, ‘I can do this. I can become what I want to become,’ that’s [their] legacy,” Crystal said.

Crystal, who works at a New Mexico school, spoke about a recent moment with her students who visited the exhibition.

“These brown kids that never have seen art in this magnitude, they were crying,” she said. “They kept saying, ‘I can’t believe Miss is her granddaughter. Oh my God. I can’t wait to go back to school when she comes so we can just sit and talk to her all day.’”

Coney-Ali also raised a point that the ongoing protests for Palestinian liberation echoed the relevance of Catlett’s work in the fight for racial justice and global solidarity.

“We have the honor of being here in this exhibition, during this political climate. Protests right outside all day today in the nation’s capital, celebrating Black legacy,” Naima said.

Naima said Catlett was and continues to be a “disruptor.”

“The fact that she chose to live the way she did, that in itself was revolutionary,” she said.

Copy edited by Anijah Franklin